This week marks one year since the Scottish Government officially declared a housing emergency. Thirteen local authorities have followed suit, confirming what many across the country already feel: Scotland is in crisis when it comes to housing.

But what does it truly mean for a government to declare an “emergency”? The definition is clear: an event or situation that poses a serious threat to public welfare, security, or the environment, requiring immediate action. And yet, for those of us working at the coalface of the housing sector—in sales, lettings, and property management—the response has felt anything but immediate.

The Numbers Behind the Crisis

Housing Demand vs Supply

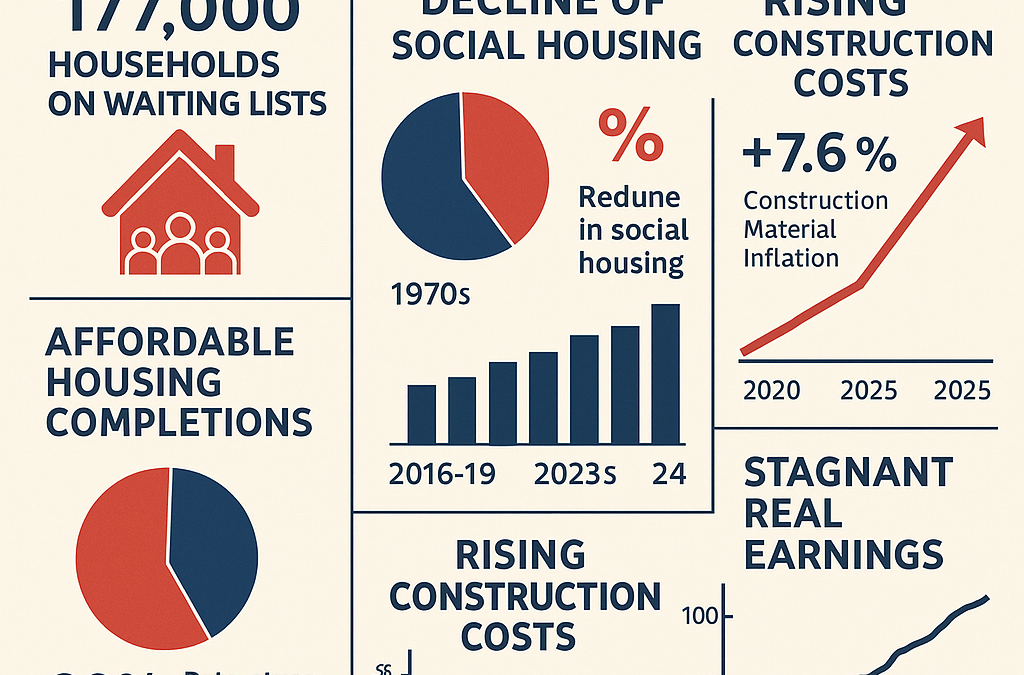

In 2023, there were 177,000 applications on local authority housing lists. Around 90,000 children are included in these numbers.

Scotland has approximately 2.72 million residential dwellings.

The government aims to deliver 110,000 affordable homes by 2032, with at least 70% for social rent.

Affordable Housing Completion (2016–2024)

Year Homes Completed

2016–17 7,493

2017–18 8,527

2018–19 9,566

2019–20 9,290

2020–21 6,479 (pandemic impact)

2021–22 9,757

2022–23 10,458

2023–24 9,680

The annual output remains far below the level needed to meet demand.

Social Housing Stock Over Time

1975: Over 40% of housing stock was social housing.

2020s: Now reduced to around 23–25%.

The long-term decline in social housing has not been reversed, despite growing demand.

Affordability: The Squeeze on Scottish Households

In 2010, the average house cost £131,901, with a median salary of £25,000—creating a house price-to-income ratio of 5.3. Today, affordability has worsened. Back in 1985, that ratio was closer to 3.5.

Meanwhile, real earnings have remained flat or grown modestly over the decades:

Year Real Earnings Relative to Today

1975 ~50–55%

1985 ~65–70%

1995 ~75–80%

2005 ~90–92%

2015 ~98–100%

Today 100%

Recent inflation and stagnating wages have diminished purchasing power, particularly in the housing market.

Soaring Construction Costs

From 2016 to 2024, construction costs have surged:

Between 2016–21: Costs rose by up to 21%.

Between 2020–22: Construction prices increased by 27%.

2023–24: Material cost increases moderated to 7.6%, but remain high.

A 2-bedroom flat in the 1970s might have cost £12,000 (~£92,000 in today’s money). Now, that same flat could cost between £180,000–£260,000 to build.

Funding: Not Matching the Rhetoric

Despite the declared emergency, government funding has fallen:

Year Affordable Housing Budget (£m)

2016–17 550.8

2019–20 839.9 (peak)

2023–24 752.0

2024–25 596.0 (22% cut)

2025–26 768.0 (restored slightly)

In real terms, spending today is lower than it was in 2017/18, despite much higher costs and a more acute crisis.

Private Rents on the Rise

In the year to September 2024:

1-bed average: £710 (+9.6%)

2-bed average: £893 (+6.2%)

3-bed average: £1,136 (+10.7%)

Regional disparities are stark:

St Andrews: £1,503 (2-bed)

Stirling: £1,025

Paisley: £808

Where Do We Live?

While 98% of Scotland’s land is rural, 71% of the population live in urban areas, with 37% in large urban centres. Land isn’t the problem—distribution and development priorities are.

Scotland in a Global Context

On average salary (adjusted for purchasing power), the UK ranks 18th among OECD nations, with countries like Luxembourg, Iceland, and Switzerland far ahead. Scotland’s cost of housing is rising, but our relative income is not.

Conclusion: A Long-Brewing Storm

This crisis didn’t arrive overnight. The seeds were planted decades ago through policy shifts like Right to Buy and the decline of small and medium-sized housebuilders—many lost after 2008.

The stats are undeniable:

Rising house prices.

Declining social housing stock.

Stagnant real wages.

Soaring construction costs.

Shrinking government budgets.

Over 170,000 waiting for affordable homes.

So, where is the “emergency” response?

No visible national task force.

No surge in planning resources.

No training drives for vital trades.

No real incentives for small builders.

No tax breaks.

No full Cabinet voice for the Housing Minister.

The numbers tell the story clearly. We may have declared a housing emergency—but without coordinated, urgent action, it remains just words.

Recent Comments